About the Book

The First Person Cogito, 2020

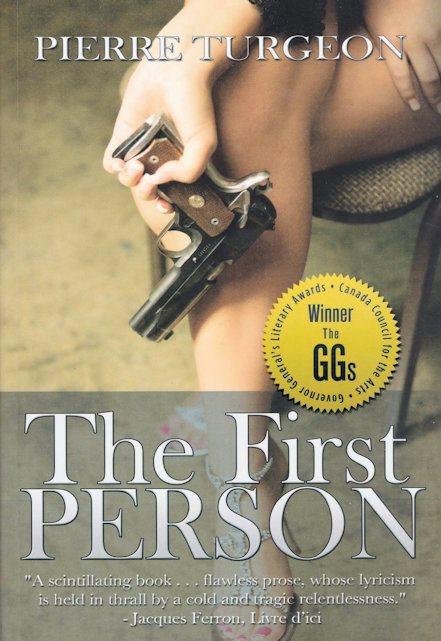

In The First Person, a disillusioned computer programmer working for the police has decided to erase his identity. We do not know why. Leaving his old life behind, the man becomes a private detective in Los Angeles under a new, forged identity. He is hired to find a local gangster’s unfaithful wife, but after locating the woman, he falls in love with her. The pair plans to reunite after he returns her and collects his fee, but their plans are shortcircuited by her husband, who punishes her cruelly for her betrayals. Devastated, the detective exacts his revenge. But soon, trapped by his own manipulations, he slowly falls into a mystic quest that redefines his self-image and world view. Written in the first person, the book explores, through the main character’s eyes, his tortured mind, and depicts, with carefully chosen words, the emptiness of his existence and his lack of real emotion. The First Person has been critically praised as an account of one man’s systematic destruction of his own personality.

The First Person

A Novel

by Pierre Turgeon

Tomorrow I leave here forever. I will take a change of clothes, my savings and the picture I took an hour ago of my wife and children. In front of my smartphone, the three of them were waving, as if they had sensed that soon I would be leaving them forever.

The eldest one was licking a vanilla ice cream, eyes hidden behind her fighting hair; the youngest one was aiming at me with a plastic Winchester: he must have killed me a thousand times in his imagination. Joëlle had raised her glasses to her forehead and smiled bravely, with a kind of desperate sweetness. They are visiting Joëlle’s parents in Quebec City for three days. I find it difficult to stay in the deserted living room. I go out for a walk. About ten bungalows like mine line up in front of the Sainte-Geneviève forest, all the way to the Rivière des Prairies. Here I am walking again. I won’t stop anytime soon, in spite of the fatigue that already suggests me to forget this story, to go home and lie down in front of the powdery light of my television set. But the street drags me along with its garbage cans scattered and empty from the passage of the garbage collectors, its children screaming behind Plexiglas goalie masks, its cars bleached by the salting of the icy streets. I walk along the CNR railroad track stretched towards the horizon between high-rise buildings and factories. I’m not sure where I’m going.

I pass without stopping, erasing forever what my eyes see, driven by an appetite for movement, anchored to my own emptiness, proud not to think, to dominate by my skin and my nerves the anxieties of the past. On a path near an ice rink, where the ice has overflowed, I lose my footing and almost fall, which makes me laugh. I catch my breath, take off my gloves, write my name in urine letters that the cold soon solidifies.

I make my way through the snow, buried up to my waist, my abdomen frozen with fear, my eyes fixed on the pulverized glare where I can guess the interlacing: dead branches broke in the fall. The silence speaks in a continuous, powerful way. Breath shortened by the effort, I lean on my thighs. In this petrified forest, rest is forbidden to me. I exist only by my movements within this whiteness ready to go straight to the heart.

Back home, I drink coffee, standing in the kitchen. I slipped my right hand on my belly, behind the belt, and tied the sleeves of my sweater around my neck. I eat a piece of chocolate cake, half closing my eyes, looking down. On the table, a jug of milk, two empty Coke bottles, an upside-down salt shaker, a laptop. I read the text printed on the cereal box. My fist clenched on the fork, as if ready to strike, I wipe the sweat from my forehead.

I crawl under the blankets and leaf through a catalog of items useful for survival in the Far North: rifles, mittens, anoraks, snowshoes, etc. I’m not afraid to get up close and personal. My father calls me. I feel compelled to listen without making inside comments, as if the other person could read my thoughts.

I hope to soon reach a foggy port where the cops flap the waves and the sirens of the tankers will give me goose bumps. As a ghost ship, I listen to the purr of the refrigerator, my nose buried in the hollow of my elbow, licking my forearm, while loneliness sets in around me as a waste of time. Will I be able to live in this extremely rarefied air? Perhaps I was only the echo of those around me?

On a pedestal table, the tarot cards testify to Joëlle’s patient search for our future. I savor the arrival of the night, the flat spread of this hour when the sun falls between a plane on the ground and the control tower of the small neighboring airport.

Life’s harsh sizzle hits against the dirty TV screen. With the remote control, I surf on hundreds of channels. But no more than in my head, I can’t get my hand in that plastic cabinet. Nothing to touch, to eat, to love. Since the first cartoons of my childhood, I’ve lived in there. My parents explained to me that in time we would see in three dimensions the giggling rabbit, the speeded-up coyote and the whole hilarious menagerie. And we would. As a child, I dreamed of the future 3D TV: I admired it in anticipation, in humans, skyscrapers, trees and cars, whose digital hues shone with incomparable intensity and purity.

The supreme wisdom is to look at the world like a commercial.

PIERRE TURGEON

Born in Quebec, October 9, 1947 – The novelist and essayist Pierre Turgeon obtained a Bachelor of Arts in 1967. In 1969, at the age of twenty-two, already a journalist at Perspectives and literary critic at Radio-Canada, Pierre Turgeon creates the literary review L’Illettré with Victor-Lévy Beaulieu. The same year, he published his first novel, Sweet Poison. Several works followed 22 titles in total: novels, essays, plays, film scripts, and historical works. These include The First Person and The Radissonia, both of which win the Governor General’s Award for novel and essay respectively.

In 1975, he founded the Quinze publishing house, which he chaired until 1978. There he published numerous authors, including Marie-Claire Blais, Gérard Bessette, Jacques Godbout, Yves Thériault, Jacques Hébert, and Hubert Aquin, before becoming deputy director of the Presses of the University of Montreal (PUM) in 1978. Then, from 1979 to 1982, he directed the editions of the Sogides group, the most important French-language publisher in America. (Les Éditions de l’Homme, Le Jour, Les Quinze). He also publishes software, launching one of the first French text editors (Ultratexte) and the first French spell-checking program (Hugo). Editor-in-chief of the literary review Liberté from 1987 to 1998, he edited controversial issues on the October Crisis and the Oka Crisis, as well as on various political and cultural subjects.

In 1999, he created Trait d’union, a publishing house devoted to poetry, essays, and celebrity biographies, works signed among others by René Lévesque, Pierre Godin, Micheline Lachance, Margaret Atwood. He is the only Canadian publisher to have seen one of his books, a biography of Michael Jackson : Unmasked, reach number one on the New York Times bestseller list. In the meantime, the author continues to be prolific, and in 2000, he published a history of Canada, in collaboration with Don Gilmor, that won the Ex-Libris prize, awarded by the Association of Canadian Booksellers with the mention of Best History of Canada to date.

Today, he is working on the creation of a publishing site entirely devoted to the distribution of English and French eBooks: Cogito, which will go live in early 2021.

Antonioni admirers take note – I admit that the most interesting thing I found about this book was the premise; a man, frustrated with his humdrum identity, assumes that of Mark Frechette. Frechette, as the novel reminds us, was the young male actor who starred in Antonioni’s ZABRISKIE POINT; he became somewhat of a revolutionary, or at the very least a criminal, after the making of the film, and was involved in bank holdups (sorry, don’t recall how many). He defended his actions in radical terms. He was arrested and sent to prison, where he tried to get several social programs going to better the life of inmates; he was a little more outspoken than was safe for him and was eventually found murdered in a weight room. All this is true, and a rather fascinating bit of recent history, particularly in that the making of the film probably had a lot to do with Frechette’s choices in later life — life imitating art and all that. It’s even more interesting that someone should then, years later, write a novel that has its main character attempting to hide under Frechette’s name. The swapping-of-identity theme — man seeking freedom from his former self, while pursued by his family — is also, of course, familiar to Antonioni fans, as a device exploited very effectively in THE PASSENGER. Alas, now that I’m hungry to reexplore it, it’s out of print. I *think* other people would find it interesting, tho’… Y’gotta admit, the premise is quite something. – Allan MacInnis – Amazon.com.

Pierre Turgeon has made a beautiful book, sparkling on a black background. A flawless prose, whose lyricism remains subdued by a cold and tragic determination, is surrounded by a deadly solitude like the pyramids of Egypt. – Jacques Ferron, Livres d’ici.

The First Person is at the same time a detective novel, a vertiginous descent into the existential void, a hallucinating portrait of what tomorrow’s world could be, if tomorrow there is, it seems to me, also a kind of sad poem, a growing economy of language that tends towards silence, inscribing in the sense as a derisory provocation, the very negation of meaning. – Réginald Martel, La Presse